Hog CAFOs Threaten Quality of Rural Life

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 2:07:57 — 61.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Podchaser | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

(October 31, 2021) What would you do if a 2,400 head hog CAFO set up shop across the street from your home? The stench would assault you and your family. You would inhale hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, endotoxins, volatile organic compounds, disinfectants, dried fecal matter and more. Your water might be contaminated. Your property values would plummet. You would not have any say about it. Even your local municipality or county board would have no power to remove the operation. Does that sound like bucolic America to you? Or does it sound as though hog CAFOs can threaten your quality of life?

Unfortunately, it sounds like Illinois. By the way, CAFO stands for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation. We’ve talked about them on our show in the past. This time, a major state aquifer might be threatened by a CAFO.

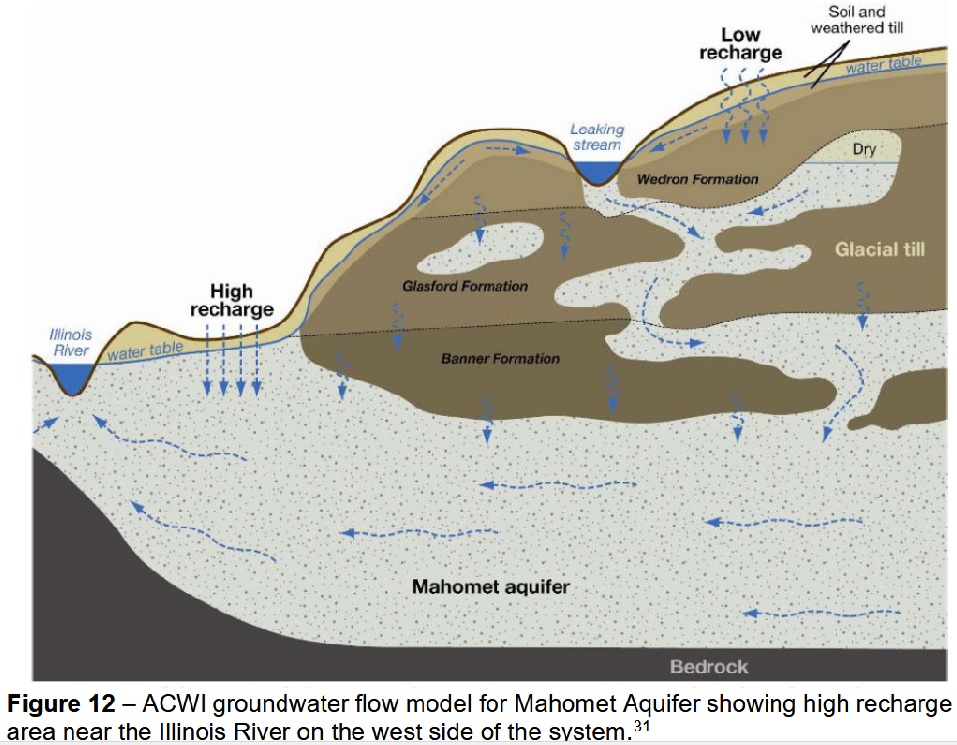

In 2015, the US Environmental Protection Agency designated a portion of the Mahomet Aquifer system in east-central Illinois as a sole source aquifer (SSA). Some 500,000 people in 15 counties rely on that aquifer as a source of drinking water. According to the EPA,

The Safe Drinking Water Act gives EPA authority to designate all or part of an aquifer as a “sole source” if contamination of the aquifer would create a significant hazard to public health and there are no physically available or economically feasible alternative sources of drinking water to serve the population that relies on the aquifer.

Hog CAFOs above an aquifer

So why is a hog CAFO being considered over Mahomet Aquifer in Mason County? This CAFO would arise between the towns of Havana and Kilbourne. Fanter Farms recently applied for a Beginner Farmer Loan through the USDA direct and guaranteed Farm Service Agency (FSA) loan program. They want to construct a 2,400 head swine CAFO. FSA must consider the potential impact on local water sources and ecology with an environmental review. This is all in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and the Endangered Species Act.

Houston, we have a problem. The aquifer in Mason County is considered “unconfined.” That means the water is close to the surface and covered by, in this case, sandy soils. In addition, the CAFO sits a half mile from the village of Peterville. Oddly, that village is not mentioned once in FSA documents. Some residents in Peterville suffer from serious health problems. To add a cherry on top, the threatened Illinois chorus frog is known to exist in the area. What could possibly go wrong?

In a seemingly parallel universe, Governor JB Pritzker recently signed SB 2515, creating the Mahomet Aquifer Council. Its purpose is to help protect this irreplaceable resource. That’s on top of the EPA’s Mahomet Aquifer Protection Task Force. In 2018, it released its Findings and Recommendations. Curiously, a search of the document turns up no mention of the words “CAFO,” “factory farm,” “pig” or “hog.” But the word “nitrate” pops up a lot.

Elevated nitrate concentrations are not a concern in most of the Mahomet Aquifer system, particularly where the aquifer is confined. In the confined region, the age of the groundwater is typically hundreds to thousands of years old. Elevated nitrate is common in the unconfined region of the Mahomet Aquifer system, in Mason and Tazewell Counties. In this region, aquifer sands are near the surface and not protected by thick glacial tills, thus the aquifer is vulnerable to contamination from a variety of land-use activities.

Also, a group called Mason County Concerned Citizens (MCCC) has partnered with Illinois Coalition for Clean Air & Water (ICCAW) and the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project (SRAP) to submit comments to the FSA about the proposed CAFO.

Twin CAFOs for twin brothers

Sounds like the title of a really bad sitcom, doesn’t it? But it’s dystopian reality. Just across the Illinois River from Mason County sits Fulton County. The brothers, Ed and Eric McEwen, want to set up two “separate” 2,480 head hog CAFOs under the name Radius Ag. Except that the facilities are basically on the same site. ICCAW’s Karen Hudson explains why that’s significant.

This highlights a common practice in new CAFO applications where CAFO barn numbers are routinely and deliberately falling ever so slightly under the “magic threshold” number of 2,500-head of swine. Any larger and the law requires the Illinois Department of Agriculture to hold public informational meetings, the evaluation of the eight (8) siting criteria that must be met before approval, and the development of waste management plans for the liquid swine manure.

So, instead of one CAFO with 4,960 hogs, there will be two CAFOs, with 4,960 hogs. But the boys get to bypass all of those nasty regulations. Neat, huh? And the Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA) is cool with that.

As if that weren’t bad enough, ICCAW did a check on a couple of Radius Ag CAFOs in yet another county. Twin barns (are you recognizing the pattern?) were built separately in Warren County in 2015. But after a Freedom of Information Act check, ICCAW discovered the facilities had no septic system! For six years! Of course, there had been no public hearing because the brothers had taken advantage of the loopholes in Illinois law. Once the violation was discovered, Radius Ag scrambled to get the septic system installed this summer. But, according to Hudson, there was no help from the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA), IDOA and the Warren County Health Department.

Who will regulate the regulators?

So, how to fight against hog CAFOs? History in Illinois shows that CAFOs usually–but not always–win. Why? To put it bluntly, in addition to power odors, they have powerful friends. That’s illustrated by Danielle Diamond, who is now a visiting fellow at Harvard Law School and was Senior Director of Research & Resources at SRAP. In a paper authored with Loka Ashwood, PhD, just released for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), they write about lack of due process.

Industrial livestock industry pressure has impacted state implementation of federal environmental protections. Attorney Danielle Diamond learned through research with anthropologist Dr. Kendall Thu that Illinois’ main environmental regulatory body, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA), failed to properly regulate CAFOs in accordance with the federal Clean Water Act (CWA) (Diamond, 2006). Rural communities felt the brunt of this lack of oversight, experiencing surface water contamination and numerous fish-kills caused by illegal discharges (Diamond, 2006). No due process for addressing illegal or harmful CAFO siting and construction permits under a different state law further exacerbates the problem (Helping Others Maintain Environmental Standards v. Bos, 2010)

A the heart of the hog CAFOs issue is an Illinois law called the Livestock Management Facilities Act (LMFA). On June 8, the Fulton County Board voted on a grassroots resolution that called for strengthening the LMFA. They’re not alone. A study by C. Nicholas Cronauer in 2011 for the Valparaiso University Law Review concluded that

The current Act lacks adequate protection for environmentally susceptible areas and permits CAFOs to threaten water sources. More restrictions around certain environmentally sensitive areas will ensure CAFOs are only constructed in suitable locations that can support its operations. A loophole enabling CAFOs to expand largely outside the Act by manipulating its construction costs needs to be closed. The setback restrictions should be narrowly tailored in order to entice CAFOs to construct more stable waste structures.

That was a decade ago, and the law has not changed. Appallingly, neither the IDOA nor the IEPA has a comprehensive list of CAFOs in the State of Illinois–whether they contain hogs or other animals. How is that even possible? Furthermore, local municipalities–including county boards–have no ability to stop those operations. It has been left to citizen-powered, grassroots organizations to mount challenges. Some have been successful, as in Winnebago County, where two 5,000 head facilities were recently stopped. Unfortunately, local groups have to face the Illinois Department of Agriculture, which has never met a CAFO it didn’t like.

Steps to stop hog CAFOs

ICCAW says that the system is broken. I couldn’t agree more. Here are some of their recommendations to fix the CAFO problem in Illinois.

• Require all concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) to register with the Illinois EPA (IEPA), so the agency actually has an accurate location database maintained. As it stands, IEPA is the agency with the primary responsibility to regulate pollution from these operations. However, the agency does not yet have an accurate accounting for all the CAFOs in the state. This is a serious public health, food safety, and food security issue.

and grassroots organizations are ofthen on their own

• Require all large CAFOs to obtain operating permits from the IEPA to prevent pollution. Currently, the IEPA generally only requires federal Clean Water Act pollution discharge permits of CAFOs IF CAFOs are caught discharging waste into surface waters.

• Close the expansion loophole under Illinois’ livestock facility siting law administered by the Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA). Under the Illinois Livestock Management Facilities Act (LMFA) and its corresponding regulations, livestock operations can more than double their size every two years without being subject to public informational meetings, setbacks applicable to new operations, and certain other siting and environmental compliance application reviews by the Department.

• Allow county boards to convene meaningful hearings and issue binding recommendations to the IDOA on the siting and construction of new large-scale livestock confinement operations. Currently, county boards can only issue non-binding recommendations to the IDOA regarding the siting of new livestock management facilities in their communities.

• Give adjoining landowners, neighbors and other impacted citizens to proposed new and expanding large-scale livestock confinement operations the legal standing to call for automatic public hearings on applications and the right to appeal poor siting decisions by the IDOA. Currently if a county board does not request a public informational meeting on a new livestock management facility proposal, 75 residents of the county must petition their county board to hold a hearing.

• Create setbacks from existing surface waters and increase setbacks from homes and towns for large facilities. Surface waters are not properly protected in Illinois and peer reviewed research demonstrates that wells, ditches and waterways near CAFOs show contamination with drug residues, antibiotic resistant bacteria, and more.

• Require all livestock facilities to submit waste management plans with spill control and a prevention plans to be approved by IDOA prior to siting and construction approvals and mandate that those plans to be subject to public review and comment as part of the application process. As it stands now, a vast majority of large-scale livestock confinement operations never have to submit their waste management plans to regulators for review and approval prior to construction or operation.

Today we welcome Karen Hudson back to the show. She is co-founder of Illinois Coalition for Clean Air and Water (ICCAW) which assists and empowers citizens on CAFO issues in over 45 counties in Illinois. She is also a senior Regional Representative for the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project (SRAP) and has worked on the intensive livestock issue nationally for over 25 years.

Chris Petersen also returns to the show. is an independent regenerative/sustainable family farmer and also a member of SRAP. He is semi retired, but still raises non-confinement antibiotic free Berkshire pigs and organic hay. He has performed front line advocacy work for 30 years against industrialized agriculture.

Kathy Martin, from Norman Oklahoma, is an engineer and technical assistant to SRAP. She has worked on CAFO issues since 1997 and has worked with communities in 25 states across the country looking at literally hundreds of manure management plans. She describes herself as a poop expert.