Seaweed Chronicles and Trout Tales

Susan Hand Shetterly is connecting nature’s dots.

![]() (August 26, 2018) I like that because it’s something that I’ve been trying to do for my audiences for more than twenty years. And every time I encounter a fellow dot-connector, I have more confidence in my own message. But this isn’t about me, thankfully.

(August 26, 2018) I like that because it’s something that I’ve been trying to do for my audiences for more than twenty years. And every time I encounter a fellow dot-connector, I have more confidence in my own message. But this isn’t about me, thankfully.

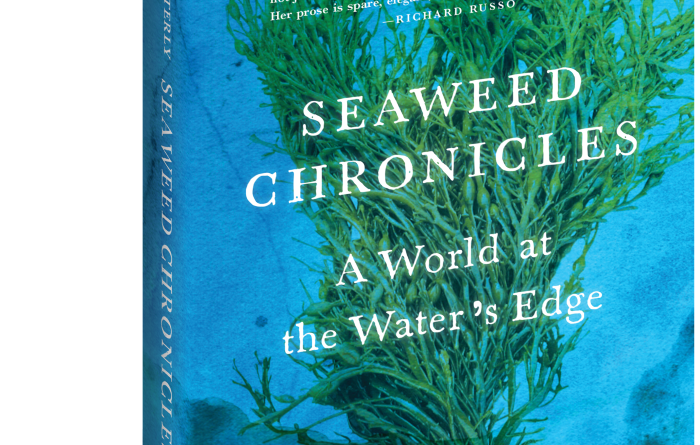

I’m quite pleased to have Susan Hand Shetterly on The Mike Nowak Show with Peggy Malecki this morning. She is the author of a just-released book, Seaweed Chronicles: A World at the Water’s Edge. And you might want to get your copy now, because I suspect that it’s going to be gathering awards, not dust.

And while the book is indeed about the biology, cultivation, commercialization and exploitation of seaweed, her brush strokes are much broader than that. Shetterly prods and pokes with questions that cut to the very heart of democracy v. capitalism, diving into the questions of corporate, communal and individual responsibility to our natural resources; the roles that science and technology play in rescuing but also destroying species; and the very serious debate about whether the human species, well into the 21st century, can finally get out of the way of its own desires to control and ultimately consume everything in its path.

That said, Shetterly does it effortlessly, carrying the reader along the way an ocean current does a fragment of Sargassum natans in the Sargasso Sea. Her prose is gentle, elegant and convincing, and she knows how to tell a story. She does so over and over again, with a cast of settlers, scientists, iconoclasts and simply strong-willed folks who have unique visions of how to preserve the best of what our planet–in this case its oceans and coasts–have to offer.

It is not until well into the book that you begin to understand that Shetterly has masterfully set up the stories to guide you to some inevitable conclusions. Among them,

The wild tests people, hones their skills, offers them a way to be in the world that can give them pride. If we can take that sort of learning and bend it toward scientific inquiry,, careful harvest, and resource protection, we will be creating something fine. The purpose of regulating the wild seaweed harvest in the state of Maine–and in the world at large–is twofold: first, to identify and protect essential habitat; and second, to build a new model of how to manage ocean resources that doesn’t edge them toward oblivion.

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not a sea guy by any stretch of the imagination. So I learned a ton of stuff reading this book. On the other hand, Shetterly makes this confession on her blog,

Over four years ago, I began research for a book about seaweeds. I knew about them only because I live by the shore, and they are a part of the daily landscape – high tide and low.

These past years of learning and writing have given me a sense of the complicated depth of wild systems and the immense value of preserving them, as well as the need for coastal people to make a living.

On the very first page, I learned something about the word algae–that microalgae are phytoplankton and that macroalgae are seaweeds. I learned that the phycologist means “algae scientist.”

I learned colorful names for various types of seaweed. For instance, Ascophyllum nodosum is called rockweed, knotted wrack or simply kelp. However, there are many other kinds of kelp, too, such as bull kelp, giant kelp, winged kelp, sugar kelp and horsetail kelp. The Fucus seaweeds are called northern bladder wrack or spiral bladder wrack or flat bladder wrack.

And I learned this about seaweed in general:

They are not plants, in the strict sense. They have no roots, no leaves, no stems. Not really. Only a few species have developed vascular tissues, and these are only sieve tubes that transport nutrients between them, not like the vascular tissues of land plants, with their complex transport of sugars from the leaves down and water and minerals from the ground up. Essential to land plants is a sophisticated coordination between specialized cells that have distinct jobs to do. When cooperation and distinctions between cells are present in seaweeds, they are much simpler. Each seaweed cell uses the water in which it lives, taking from it the nutrients it needs.

And yet, those water-based non-plants can be chock full of nutrients, which is why they are harvested and used as food or food supplements in many societies.

Here in the United States, though, we just starting to investigate this natural resource. But it is happening partly as a result of the depletion of fishing stock in the Atlantic Ocean.

We’ve worked our way through whales, bluefin tuna, halibut, cod, haddock, herring, lobsters, scallops, soft-shelled clams and bait worms–on and on–and finally to harvestable habitat, and that habitat is seaweed. Some people call this “feeding down the food chain”: you harvest the wild creatures the land or water provides, starting with the largest, and end up eating the smallest creatures or, in this case, their habitat.

I call it terrifying. And I’m not the only one especially in light of a battle raging this very moment on the Maine shores over who has the right to harvest rockweed.

The fight has tumbled into the courts, and there taken another peculiar turn. The Maine Supreme Court is now pondering whether seaweed is a plant — which would make it the property owners’ — or an animal, which would mean it could be harvested by anyone, like fish from the sea.

The Supreme Court may be wringing its hands, but it’s not a tough call for David Garbary, a professor of biology at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia who has studied this seaweed for 30 years and laughs at the issue.

“This is one of those absurd questions where you get tied up in definitions that are not relevant,” he says. “This is a perfectly good photosynthetic organism, and it’s a plant.”

But in the very best tradition of environmental journalism, Shetterly makes the case for optimism. I hope she’s right. It’s a pleasure to have her on the show this morning.

There’s nothing fishy about science

We really didn’t plan to have most of today’s show be about seaweed or fish. Honest! Sometimes, those are the quirks of scheduling. But somehow, it seems to make sense. And the headline below is the one used in an article by Christopher Johnson, who was a guest on the show on June 18, 2017 (to weigh in on a completely unrelated topic). In the 2018 story in Chicago Life, he writes about

Trout in the Classroom (TIC) program, a nationwide environmental education program for Grades K-12 that teaches schoolchildren about trout and the cold-water waterways they inhabit. It’s a highly innovative, hands-on curriculum that brings young people into environments that many of them have never experienced before Trout Unlimited (TU), a national conservation organization dedicated to protecting and restoring trout populations and their habitats, has partnered with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) to bring the TIC program into schools throughout the Chicago area. Marvin Strauch, the Education Chair for TU’s Oak Brook Chapter and a member of the organization’s Illinois Council, says, “There are 26 programs going on in the state of Illinois. They’re all in the metropolitan Chicago area. There are four TU chapters in Illinois. Each one of those chapters is participating with multiple schools.”

Trout in the Classroom (TIC) program, a nationwide environmental education program for Grades K-12 that teaches schoolchildren about trout and the cold-water waterways they inhabit. It’s a highly innovative, hands-on curriculum that brings young people into environments that many of them have never experienced before Trout Unlimited (TU), a national conservation organization dedicated to protecting and restoring trout populations and their habitats, has partnered with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) to bring the TIC program into schools throughout the Chicago area. Marvin Strauch, the Education Chair for TU’s Oak Brook Chapter and a member of the organization’s Illinois Council, says, “There are 26 programs going on in the state of Illinois. They’re all in the metropolitan Chicago area. There are four TU chapters in Illinois. Each one of those chapters is participating with multiple schools.”

Marvin Strauch, mentioned above, joins us on the show this morning. He’s a business owner who lives on the southwest suburbs of Chicago, and he’s been an avid fisherman for his entire life. In 2000, he joined Trout Unlimited in 2000, and is a past president of the Oak Brook Chapter – representing the west and south suburbs of Chicago as well as much of downstate Illinois. But the real reason he’s in the WCGO studios today is because he’s the Trout in the Classroom Coordinator for Illinois. He tells us that

Trout Unlimited is the nation’s largest Coldwater conservation organization, with over 300,000 members in 400 local chapters. Our mission is to preserve, protect, and restore North America’s Coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. TU is both a national environmental group with national staff, and advocating for large scale environmental issues, and heavily a grass roots organization, with the members of those 400 chapters actively involved in conservation projects to Coldwater streams in their area.

Joining Marvin this morning in the studio is Joe Lentino a Trout in the Classroom teacher in the Chicago Public Schools. Joe is a Chicago native, who has been a science teacher for 10 years at Burroughs Elementary. He says he became interested in conservation through the Boy Scouts and family vacations in US national parks and is now working to increase opportunities for youth to participate in outdoor recreation and environmental stewardship.

I can’t wait to discuss their hands-on approach to teaching kids about Science! Get ready for some sound effects.