Midwest Derecho Aftermath

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:30:52 — 41.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Podchaser | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

(August 23, 2020) On the afternoon of August 10, 2020, I stood on my front porch as the tornado sirens blared in the Logan Park neighborhood of Chicago. The skies were darkening. The wind was picking up. I took out my cell phone and sent a live stream to Facebook, a video that more than 750 people would eventually watch. I took my hanging plants down and placed them on the floor of the porch. Suddenly, the gusts intensified dramatically and I knew it was time to get inside. Two weeks later, millions of people are living with the Midwest Derecho Aftermath.

Skip to a specific segment in this podcast

7:54 Diane Blazek of National Garden Bureau

23:45 Ryan Anderson from Midwest Grows Green

46:27 Journalist Lyz Lenz and meteorologist Rick DiMaio

1:09:32 Alder Scott Waguespack and Daniella Pereira from Openlands

1:22:18 Meteorologist Rick DiMaio

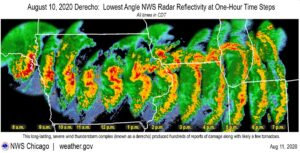

I knew that bad storms were on the way because our resident meteorologist, Rick DiMaio, had been sending warnings all day long. To get a sense of the history of the events of August 10, check out amazing and comprehensive report from the National Weather Service. Just looking at the progression of the storm as it rolled from eastern South Dakota and Nebraska, through Iowa and Illinois and Wisconsin, then into Indiana, Michigan and Ohio, is awesome. I don’t mean in the sense of “cool.” I mean one is in awe of the power of nature.

I knew that bad storms were on the way because our resident meteorologist, Rick DiMaio, had been sending warnings all day long. To get a sense of the history of the events of August 10, check out amazing and comprehensive report from the National Weather Service. Just looking at the progression of the storm as it rolled from eastern South Dakota and Nebraska, through Iowa and Illinois and Wisconsin, then into Indiana, Michigan and Ohio, is awesome. I don’t mean in the sense of “cool.” I mean one is in awe of the power of nature.

This kind of storm is called a derecho. The NWS explains.

Although a derecho can produce destruction similar to that of a tornado, the damage typically occurs in one direction along a relatively straight path. As a result, the term “straight-line wind damage” sometimes is used to describe derecho damage. By definition, if the swath of wind damage extends for more than 250 miles (about 400 kilometers), includes wind gusts of at least 58 mph (93 km/h) along most of its length, and also includes several, well-separated 75 mph (121 km/h) or greater gusts, then the event may be classified as a derecho.

More from NWS.

Over 700 reports of severe wind speeds (58+ mph) or wind damage from the Nebraska/Iowa border, across Iowa, northern Illinois, and northern Indiana. This was a high end, once-a-decade type event for the area.

Over 700 reports of severe wind speeds (58+ mph) or wind damage from the Nebraska/Iowa border, across Iowa, northern Illinois, and northern Indiana. This was a high end, once-a-decade type event for the area.- Over 150 of the wind reports are from all of northern Illinois and northwest Indiana.

- 6 injuries were reported in the NWS Chicago CWA, 5 being in Forreston, IL and 1 in Peru, IL.

- In the NWS Chicago County Warning Area, 15 tornadoes were confirmed, which includes portions of northern Illinois and northwest Indiana. As of this time, this count ties August 10, 2020 with June 22, 2016 as the single calendar day with the 2nd most tornadoes within our county warning area (behind the 6/30/2014 “Double Derecho” event).

- In total, the derecho produced 20 confirmed tornadoes across Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana.

- The tornadoes include an EF-1 tornado in Rogers Park, Illinois (a north-side neighborhood of Chicago), that moved out over Lake Michigan and became a waterspout. This was the first tornado in the city of Chicago since September 3, 2018 (EF-0). This was the first F-1/EF-1+ tornado in the city of Chicago since May 29, 1983 (F-1) just east of Cicero Avenue near Hawthorne Race Course. The last time a stronger tornado occurred in the city was an F-2 on March 12, 1976 that clipped the far northwest side of the city, roughly near O’Hare Airport and Edison Park.

That last part is for all of those folks who think that tornadoes cannot hit major metropolitan areas. But the storm seemed to do its worst damage in Iowa. There, the Midwest derecho aftermath was apocalyptic. The Cedar Rapids Gazette reports that the storm “caused an estimated $4 billion in damage statewide, according to the state’s federal disaster assistance request. Wind speeds exceeded 100 mph across Iowa as the storm passed through the state from nearly river to river.” For the geographically-challenged, that means from the Missouri River on the west to the Mississippi River on the east.

Farmers took big hits across several states, but especially in Iowa.

Something that caught my attention was a series of columns by Gazette opinion writer Lyz Lenz. Interestingly, the first piece I saw was not in the Gazette, but in the Washington Post, under the headline, An inland hurricane tore through Iowa. You probably didn’t hear about it. That got my attention. Lenz writes,

Gusts of 112 mph were recorded in Linn County. As I drove through the town of Cedar Rapids on Monday, I saw billboards bent in half, whole buildings collapsed, trees smashed through roofs and windows. The scope and breadth of the disaster is still being calculated, but by some estimates, more than 10 million acres, or 43 percent, of the state’s soybean and corn crops have been damaged.

A quarter of a million Iowans are still without power. In Linn County, where I live, 79 percent of people are without power, still, three days after the disaster. Cell service is spotty, where it exists. The few gas stations and grocery stores with power only take cash. And good luck getting cash from your bank, which is most likely closed. Even if you have the money, lines snake around the gas stations, two hours long or more, and the grocery stores are chaos. A citywide curfew exists. You can see the Milky Way from the darkened downtown.

All during a pandemic that has claimed 175,000 lives across the country, by the way. I’ve been to Linn County. I spoke at a gardening event in Cedar Rapids a few years ago. Words like the ones Lenz wrote hit harder when you have first hand knowledge of an area. That’s called sympathy. But if you’ve never been to Linn County and those words tear at your heart, that’s called empathy. Something our present national administration would need to purchase, as they don’t seem to be capable of calling it up from whatever is left of their souls. But I digress.

As I began reading more of what Lenz has been writing in the past couple of weeks, I knew I wanted her to be on this Sunday’s show. Just Friday, August 21, she asked Why did it take so long for help to arrive after Iowa storm?

At the Blairs Ferry Senior Apartments, residents said they went without power for four days. Power remained intermittent and residents were encouraged to bring their cellphones with them in case they got stuck in the elevator.

At the Linwood Apartments, residents still were without power as of six days after the storm.

In the absence of a coordinated, centralized response to the disaster, people in Cedar Rapids have just done it themselves — organizing and mobilizing on Facebook.

We aren’t new to disaster. This is the third major natural disaster in 12 years. Each time, residents organized and collaborated to help one another through social media. But the efforts, while herculean and well-intentioned, have blind spots.

Those “blind spots” led to 16,000 people without power ten days after the storm. 5,000 people are still without power on Saturday, August 22. By the way, if you want to help, The Gazette has a raft of organizations that you can contact.

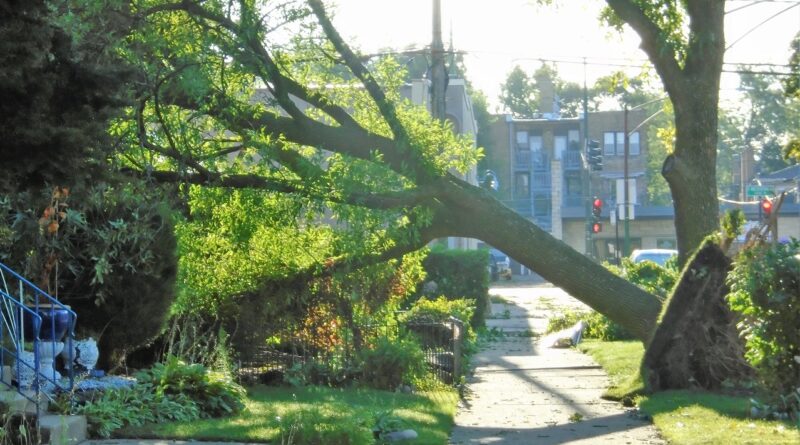

As the storm moved east, the Midwest derecho aftermath was still severe, but not debilitating. By the time the storm hit Chicago, it seems as though the straight line winds were less severe, but the storm was spinning off tornadoes. One of them hit Rogers Park, where I have many friends. In fact, one of those friends took the photos that are displayed in this blog post. He didn’t want any photo credit.

As the storm moved east, the Midwest derecho aftermath was still severe, but not debilitating. By the time the storm hit Chicago, it seems as though the straight line winds were less severe, but the storm was spinning off tornadoes. One of them hit Rogers Park, where I have many friends. In fact, one of those friends took the photos that are displayed in this blog post. He didn’t want any photo credit.

I saw another article in a different newspaper four days after the storm. It was an opinion piece written by Daniella Pereira, who was on our show about seven months ago. She is Vice President for Community Conservation at Openlands. She is also a certified arborist, who has worked in forestry for nearly 20 years. Pereira writes,

Chicago is on track to lose the greatest number of trees ever in one year. Before the recent derecho storm, public records show removals neared 7,300 trees. Mayor Lori Lightfoot said the storm took out that same number of trees in one afternoon. That’s a total of 14,600 trees lost in 2020, with 4½ months to go.

Sadder still is that many of these downed trees could have been saved with consistent care. These trees should have been part of a maintenance cycle in which they are inspected and pruned regularly, improving efficiency, lowering costs and reducing the need for 311 requests.

A few weeks ago we urged people to contact their Chicago aldercritters to have them support an Urban Forestry Advisory Board. According to Pereira,

The board would bring changes by advancing better policies and practices to care for trees and coordinating city agencies that can impact the health of trees. It would also identify opportunities to supplement public with private funds by better coordinating efforts with nongovernment partners and volunteers that work with trees. The board would be made up of department commissioners, industry leaders and community members that represent the full breadth of Chicago’s diverse communities.

That proposal made it to Chicago City Council, but ended up in the dreaded Rules Committee. That’s basically where City ordinances go to die. So I contacted Alder Scott Waguespack. Since the election of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, he has become chair of the powerful Finance Committee. He told me that “Ald. [Michelle A.] Harris at Rules will be sending it back to Finance Committee so we can get a hearing date booked w/ all the potential actors.” He also sent me an link to an interesting letter to the editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, where he is called out for stating, “We maintain an inefficient tree-trimming system, lose trees due to disease and opaque removal processes, and reinforce long-standing inequities in the delivery of city services.”

This morning, we bring all of these stories together in the second hour of the show. We’ll start with our own Meteorologist Rick DiMaio and Lyz Lunz of The Gazette, who will address the larger issues of the derecho. Then Daniella Pereira and Alder Scott Waguespack discuss the future of a possible Urban Forestry Advisory Board. This should be good.

Happy 100th, National Garden Bureau!

We start the first hour of today’s show with a man named James H. Burdett. In 1920, following World War I, he recognized that Americans needed more instruction in backyard gardening. It didn’t hurt that he was the advertising manager of a seed company and a former newspaper journalist. His idea was to get horticultural writers and broadcasters together to educate the public. Thus was born the National Garden Bureau (NGB).

It has survived a second World War, the atomic age, computers, social media, and it will likely survive COVID-19. One of the highlights of the organization came during WWII, when Burdett’s book, The Victory Garden Manual, was published in 1943 to aid home gardeners in creating a successful garden. Fast forward 77 years, and the NGB has presents Victory Garden 2.0. Click on the link and you will find ten steps for planting your own Victory Garden. NGB says that all credit goes to James H. Burdett.

When the Victory Garden Manual was first written in 1943, it was pretty easy to come up with reasons to grow your own vegetables. It was wartime and food was scarce. The food that was available might not have been the freshest or healthiest. Statistics say that in 1943, nearly 40% of all fruits and vegetables grown in the U.S. were grown in-home and community victory gardens. That’s impressive!

When the Victory Garden Manual was first written in 1943, it was pretty easy to come up with reasons to grow your own vegetables. It was wartime and food was scarce. The food that was available might not have been the freshest or healthiest. Statistics say that in 1943, nearly 40% of all fruits and vegetables grown in the U.S. were grown in-home and community victory gardens. That’s impressive!

Now, as National Garden Bureau celebrates its 100th anniversary (1920-2020), it seems timely to reintroduce the concept of victory gardening with quick and easy steps to plan and grow your own vegetable garden.

In addition NGB just completed its “Future of Gardening” survey. Personally, I’d just like to get through 2020. You can ask me anything you want next year. However, we welcome Executive Director Diane Blazek back to the show to talk about the survey results, Victory Garden 2.0, and what this pandemic year has meant for her organization and gardening in general.

Late August is Lawn Care Time

Peggy and I received an email from another friend of the show this week. Ryan Anderson is Community Outreach Specialist for Midwest Grows Green (MGG). They are a collective of community-based lawn and landscape care initiatives, which are identified by their orange MGG stamp and unified by a single message – protect people, pets and the environment by practicing natural lawn care.

Anderson wrote,

Midwest Grows Green is excited to offer one community in the Greater Chicago region FREE technical assistance for the implementation, improvement, and marketing of natural lawn care for up to two turfgrass fields. Starting this fall, our team will assess the fields of the chosen applicant, conduct soil tests, and offer an extensive set of plans, recommendations, and resources to manage the chosen turfgrass fields with no synthetic pesticides and fertilizers for up to three years. Want to learn more? Visit the Google form application at bit.ly/MGGapp2020. Application deadline is Friday, August 28th at 5 pm CST.

This is a good time to be talking about lawn care in the Midwest because fall is universally recognized as the best time to plant cool season grasses, which are what we grow here. One of the MGG partners is a company called Good Nature Organic Lawn Care, based in Cleveland, Ohio. The founder is Alec McClennan, who writes,

Back in high school, my Biology Teacher taught us about the problems caused by lawn fertilizers and chemicals in a local trout stream. Later that year, my dad asked me to spread a popular weed & feed on our lawn. After reading all the hazardous ingredients, I refused. My dad agreed to take back the fertilizer, but told me I had to find another way to keep the lawn looking nice. And so began my passion for Chemical Free Lawn Care.

Twenty-one years later, the business has locations in Cleveland, Akron, Columbus and Indianapolis, Indiana. In preparation for today’s conversation, McClennan told me to look at piece on his website–

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid, usually shortened to 2,4-D, is a very common weed killer that does not affect many grass species. It serves as the main active ingredient in many weed and feed products, such as Ortho Weed B Gon, Spectracide, and Weedone.

While this herbicide does kill undesirable plants, it also drifts easily and kills nearby plants, that were otherwise not problematic. Furthermore, like Roundup, 2,4-D is toxic to aquatic life, as well as birds, bees and your pets. Dogs raised in lawns with higher levels of 2,4-D have increased incidents of cancer. If ingested or rubbed on the skin, this chemical can make someone very sick. Some of the side effects include; coughing, burning at the site of contact, dizziness, loss of muscle coordination, nausea, diarrhea and vomiting. It can also cause nerve system damage, gene mutation, and is linked to endocrine system damage, including decreased testosterone and ovulation changes that negatively affect reproduction.

I’ve been preaching that story for about as long as McClennan has been running his business. Nice to have some company, though.

Ryan Anderson and Alec McClennan join us on the show today, to encourage your community to apply to get a couple of fields switched to organic practices. But we’ll also get a jump on lawn care season, which starts right NOW!