Plastics Mess on Aisle 2 in the Green Industry

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 2:01:17 — 56.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Podchaser | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

(March 7, 2021) Item #1: We have a plastics crisis on our planet. Item #2: On this show, we talk about growing things. Those two items might seem unrelated. However, if you understand that the horticultural industry relies on plastics for its growth, the connection is clear. Which is why, on this week’s show, we’re looking at the plastics mess on aisle 2 in the green industry.

As National Geographic reports, our plastics problem is…well, a problem. Here are a couple of facts that might cause a sleepless night or two.

- Production increased exponentially, from 2.3 million tons in 1950 to 448 million tons by 2015. Production is expected to double by 2050.

- Every year, about 8 million tons of plastic waste escapes into the oceans from coastal nations. That’s the equivalent of setting five garbage bags full of trash on every foot of coastline around the world.

Here’s another statistic, but it doesn’t come from that National Geographic article. And it’s about a specific use of plastics.

Most plants are now sold in single-use, petroleum-based plastic pots. Large growers and nurseries each process tens of millions of plastic pots in one season. As we have seen, in 2018, 180,516,000 potted annuals and 146,619,000 potted perennials were sold.

You do the math. Okay, I’ll do part of the math and tell you that the total number of plants sold in 2018 was 327,135,000. Most of those were in plastic containers. And, after those plants were put in the ground, about 95% of the containers were dumped into landfills. I got that information from a white paper called Plastic Pots and the Green Industry: Production, Use, Disposal and Environmental Impacts.

That report was written in 2020 by Marie Chieppo, a designer, gardener and horticulturalist, who runs EcoPlantPlans, LLC in Needham, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston. It was published by The Association of Professional Landscape Designers (APLD).

But we’ve been talking about the plastics mess in horticulture for more than a decade. Back in 2009, friend of the show and horticultural writer Beth Botts wrote an article for the Chicago Tribune with the headline, Push is on to green up the gardening industry. At that time, she wrote,

James Garthe, an agricultural engineer at Penn State University in University Park, Pa., estimates that only about 1 percent of the plastic used in the agriculture industry — including horticulture — is ever recycled. Compare that to the 23.5 percent of the plastic in soda and water bottles and 26.4 percent of the plastic in milk jugs that were recycled in 2006, according to Jennifer Killinger of the American Chemistry Council in Arlington, Va. A major factor: Unlike the nursery industry, those containers are made from standardized types of plastic resin that are clearly marked, making it easier to collect and separate them so recyclers can get a usable quantity of a single plastic product.

She followed up five years later with this story: Beauty and the plastic beast.

Much garden packaging doesn’t even carry a recycling code — the number in a triangle that is used to classify plastic for recycling. And even when it does and a gardener puts it in the recycling bin, the small quantities collected of each kind probably mean that plastic will be part of the “residual” that leaves the recycling center for a landfill. Many recycling programs don’t take the No. 4, 5 and 6 type plastics used in most pots, or discard them because they have soil clinging to them.

The one thing she mentions in both articles is the rising price of oil. Well, Chieppo reports that a lot has changed in seven years.

Until recently, the cost of making plastic products from recycled flakes was cheaper than relying on virgin plastics made using fossil fuels, so the economics made it easy to choose the sustainable option. At present, however, there is little to no incentive to recycle plastic. Producers have sharply increased virgin plastic production, further driving down prices. In large part, the market for recycled plastic has disappeared.

Unfortunately, while the price of fossil fuels has declined dramatically, it has led to little incentive to recycle plastic. Most plastic horticultural pots–an incredible 95%–still end up in landfills.

While it is possible for our industry to reduce and recycle, doing it on a large scale is extremely challenging. Recycling has not worked well. Plastic pots require a tremendous amount of effort and expense to collect, clean and transport. The number of facilities available to recycle them are inadequate. Once they do reach a facility, most used pots do not even reach the conveyor belt; they are rejected at the sorting stage. Until facilities on a larger scale invest in new technologies, black pots, the majority of types, will be rejected. Re-use of plastic pots is also exceptionally limited, due to difficulties in collecting and cleaning pots, degradation of the plastic, and risks associated with leaching after multiple uses.

Stir in a depressed recycling market and a global pandemic, and it’s not surprising that recycling efforts have stalled. So why not just reuse pots?

• UV light degradation reduces the flexibility of plastics and makes them more breakable and harder to handle.

• Worn pots are less attractive to the consumer, and so affect sales.

• Collection of the pots is challenging due to the variety of pot sizes, shapes and variety of resins.

• Pots may be contaminated with pesticides or plant pathogens and must be cleaned. A failure to do so deems them

unrecyclable and raises legal liability issues.

• The logistics of getting used pots back to the grower for reuse can be difficult.

• The low cost of new pots and their ready availability in the market make them the preferred choice for growers who are

justifiably focused on their bottom line.

There’s so much more to discuss. I urge you to read Chieppo’s white paper, which I’m linking again here: Plastic Pots and the Green Industry: Production, Use, Disposal and Environmental Impacts. Meanwhile, we talk about the plastics mess in the horticultural world and possible solutions on today’s show with Marie Chieppo.

Bees, bikes and Hippeastrums

At the end of last year, I received an email from horticultural buddy and activist Qae-Dah Muhammad. When I write “activist,” I’m not kidding. And neither is she. Not only is Qae-Dah is president of the Arthur Ashe Beach Park Advisory Council, she is founder and manager of the Chicago South Shore Farmers Market.

One thing I did not know is that Que-Dah is a beekeeper. In her email, she wrote about growing her Hippeastrum (known to most people as Amaryllis). Then she surprised me by writing about her beekeeping.

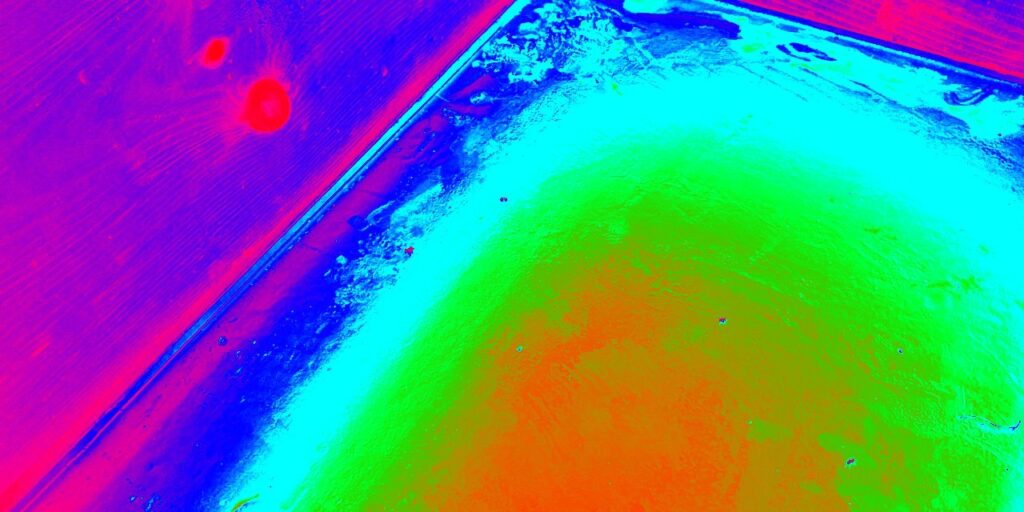

Also, I’m practicing thermography on my beehive. I’m using thermo imaging camera to monitor their activities in the hive.The yellow jackets almost robbed this colony out of existence this summer. So they have far less bees than needed to overwinter. So the red indicates the cluster bees form to keep themselves and the queen warm. That’s awesome as long as they generate heat. They have an insulated vinyl cover and a good blanket of snow will soon add another layer of insulation, a winter bee kind candy board to supplement their food is inside the hive. My fingers are crossed, I’m determined to get this colony through winter.

You can see the image of her thermal imaging on the right. What I also did not know is that the hive was located at a place called the #LetUsBreath Collective #BreathingRoom Space in the Back-of-the-Yards neighborhood.

So, I said, “Let’s talk bees on the show.”

She said, “I’m not a bee expert.”

I said, “We’ll get one.” And as these things often happen, I saw a notice about a business called Bike a Bee on Chicago’s south side. They have been on my radar for awhile, because of their mission:

Bike a Bee is an urban beekeeping project with about 40 hives on the south side of Chicago, with a few more scattered around the north and west sides. Most of our hives are placed in community gardens, schools, urban farms, and other shared, visible spaces. We believe having bees where people can see them enriches the community’s understanding of bees and the natural systems around them; children, teens, and adults learn through observation and coexistence that bees are our friends, not our enemies!

We also believe that having a car is not necessary to be a productive beekeeping project. We bike to our hives for weekly inspections, equipment delivery, and honey harvest. By going by bicycle, we are able to slow down and better observe what is growing around us, wave to neighbors, and get in some good exercise.

Jana Kinsman is the founder, owner and biker for Bike a Bee. Today, we’ll talk about Que-Dah’s efforts to keep her bees alive this winter, as well as what the prognosis for honey bees throughout the Midwest.

Still fighting for a right to garden

If it’s a new year, then it must be time for another visit from a gardener fighting for justice. I’ve told this story a number of times, so I’ll just repeat what I wrote for our show in October of last year.

In 2017, Nicole Virgil appeared on our show to talk about a fight she had been having with the city of Elmhurst, Illinois for two years. The issue was a hoop house in her family’s backyard, constructed to extend their growing season. Sustainability in action, right? But the city told them to take it down because it violated some kind of ordinance about allowed structures. As she writes, “The City of Elmhurst applied the permanent building code to the Virgil family’s temporary membrane structure to claim it’s illegal, while allowing other membrane structures all over town.”

When she stopped by again last year, that issue had not been resolved. That was after three city council meetings, five development planning meetings and three zoning and planning commission meetings. Getting frustrated with lack of response from her own municipality, Virgil decided that it was time to get serious. She created the Right to Garden website and YouTube channel. And she went to the Illinois General Assembly.

But those bills expired when last year’s General Assembly closed shop. With the start of a new year, there are new bills.

Late last week, Rep. Sonya Harper filed the Illinois Vegetable Garden Protection Act (HB 633), which would preserve and protect the right of all Illinoisans to “cultivate vegetable gardens on their own property, or on the property of another with the permission of the owner, in any county, municipality, or other political subdivision of this state.” The Act would protect the right to grow vegetables, as well as “herbs, fruits, flowers, pollinator plants, leafy greens, or other edible plants.” For many Illinoisans, this reform has been a long-time coming, as similar measures have come close to passage in prior sessions. A companion bill (SB 170) has also been introduced by Sen. David Koehler.

And, in addition to the Illinois groups that are already behind Nicole Virgil, there’s a new partner–the Institute for Justice. IJ explains that the proposed law would

- Prevent municipalities from banning vegetable gardens

- Protect the right to grow vegetables, including herbs, fruits, flowers, pollinator plants, or other edible plants

- Require municipalities to regulate gardening structures equally to other legal structures.

Sounds kinda reasonable, doesn’t it? I guess, unless you’re a City of Elmhurst official. IJ also notes that the law would make Illinois a national leader in the local food movement. I think I’d like that.

Attorney Ari Bargil at the Institute for Justice joins Nicole Virgil on our program today to chart the progress of the new Illinois bills. As always, you can find more information at https://www.righttogarden.com/, as well as their Facebook and YouTube pages.