August 7, 2016 – The Air We Breathe and the Insects That Fly In It

Kathleen Thompson and the Mold Report

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time outdoors, you’re probably very aware of any sensitivity you might have to weed, tree or grass pollen. You might not be so aware of one of the biggest problems during the growing season in the Midwest—mold. Starting in the spring and usually peaking the October, mold causes problems for a lot of people in the Chicagoland area, which is ranked third in the nation among the worst cities for mold allergies by Indoor Restore Environmental Services. (Their ratings use data from the Allergy and Asthma Foundation of America and Quest Diagnostics.)

Mold can cause an allergic reaction that is very similar to that caused by pollen—sneezing, itching, runny nose, congestion and dry, scaling skin. Or it can go into the lungs and trigger an asthmatic reaction—difficulty getting a breath, a tight chest, coughing at night, possibly wheezing. One result of the latter symptoms is that you don’t get enough oxygen and may suffer from exhaustion, difficulty concentrating and drowsiness. If you have never been diagnosed with asthma, these symptoms can feel a lot like anxiety and depression.

Writer Kathleen Thompson–who just happens to be part of The Mike Nowak Show team– joins us to talk about how a sensitivity to mold can seriously reduce your enjoyment of gardening and other outdoor activities and why this year is particularly brutal. She’ll let you know how you can monitor mold activity at the National Allergy Bureau™ (NAB™) and what steps you can take to make life more livable.

Doug Taron and respect for insects

If it’s summer in the Midwest, it’s time to be obsessed by insects. A few weeks ago, I saw a story that Cecil Adams wrote in The Straight Dope called Why Are Humans So Afraid of Insects? Good question, Cecil. Unfortunately, he wasn’t exactly able to answer it.

A couple of weeks later, there was this one in Triple Pundit: A Growing Crisis: Insects are Disappearing–And Fast. Hmm. That can’t be good news, unless you’re entomophobic. Look it up.

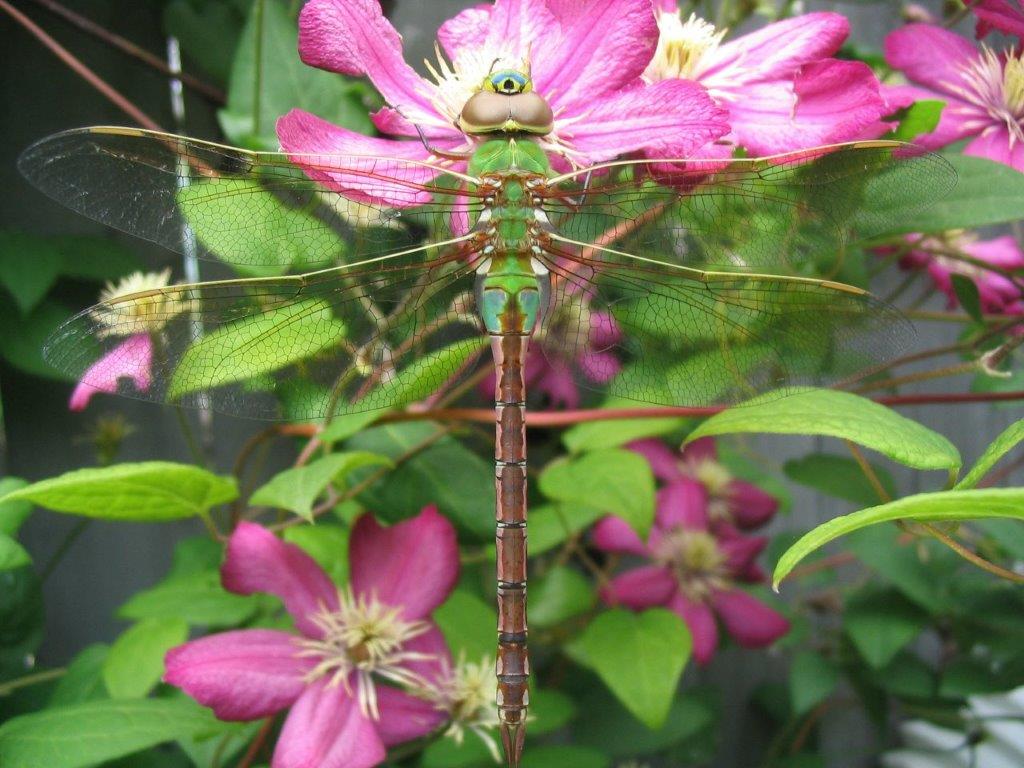

Then, just a couple of days ago, this one showed up in DNA Info Chicago: Giant Dragonfly Swarms Are Taking Over Chicago, But Don’t Be Afraid. Explain how to keep calm to all of the entomophobic people in your building.

I took this photo in my garden a number of years ago, thinking it was an extremely exotic species. Now I realize that it’s just a green darner, one of the most common dragonflies in Chicago. Sigh…

I took this photo in my garden a number of years ago, thinking it was an extremely exotic species. Now I realize that it’s just a green darner, one of the most common dragonflies in Chicago. Sigh…

Instinctively, I knew it was time to call upon the go-to guy for bug questions in Chicago–Doug Taron, curator of biology at Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, who hasn’t been on my program for a couple of years, so he was overdue. I’ve heard him called “The Butterfly Guy” but his reach is obviously much greater than that. In fact, I discovered from the DNA Info story that he’s an administrator with the International Migratory Dragonfly Partnership.

Well, I didn’t know that there was such a thing and I certainly didn’t know that certain dragonfly species–like monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus)–have annual migrations. Well, maybe bi-annual migrations. Or not. It’s hard to know because we haven’t studied them as extensively as the monarch butterfly. Which makes me laugh because it wasn’t until the late 1970s that we even knew where monarchs overwintered in Mexico. We haven’t exactly studied them with laser-like intensity either. At least not until they started to disappear.

Which brings us to a paper that Taron and some colleagues had published in 2015 about how we monitor monarch populations and what that means for interpreting their decline. They suggested that when and where you monitor monarch populations has a bearing on how you interpret the health of the species.

Monarch on a butterfly weed (what else?) at

Monarch on a butterfly weed (what else?) at

Wilmette Centennial Park Prairie

Well, that led to a rebuttal from another team of scientists, which led to a “rebuttal of the rebuttal,” as Taron puts it, and more. You can read the papers for yourself here, here, here and here.

Here’s the point. We’re still figuring out what’s happening to the monarch. We think they’re in decline but what we might be witnessing is a variability in numbers that has been happening for centuries. The loss of milkweed might be significant…but it might not be, either. That’s what scientists do. They suggest theories based on the best science available and then they punch each other a bit until the best theory wins.

Meanwhile, Doug points out that there are other species of butterfly out there–like the Baltimore checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton), which he is attempting to reintroduce to Bluff Spring Fen in western Cook County, after it disappeared about four years ago.

And he cares about moths, too, including a stem-boring moth called Papaipema cerina, which doesn’t seem to have a common name, which is just sad. Anyway, he may or may not have successfully introduced it to Bluff Spring Fen in the early 1990s, as its numbers were dwindling in northeastern Illinois and in other parts of the U.S. as well. Now he’s trying to determine whether the moth has survived there for almost 25 years.

Doug is also excited about the Regal Fritillary being listed as one of 12 so-called “priority species” in this region by Chicago Wilderness. Monarchs are also on that list, and it’s something else we’ll talk about this morning.